DnaJ mediates phage sensing by the bacterial NLR-related protein bNACHT25

Abstract

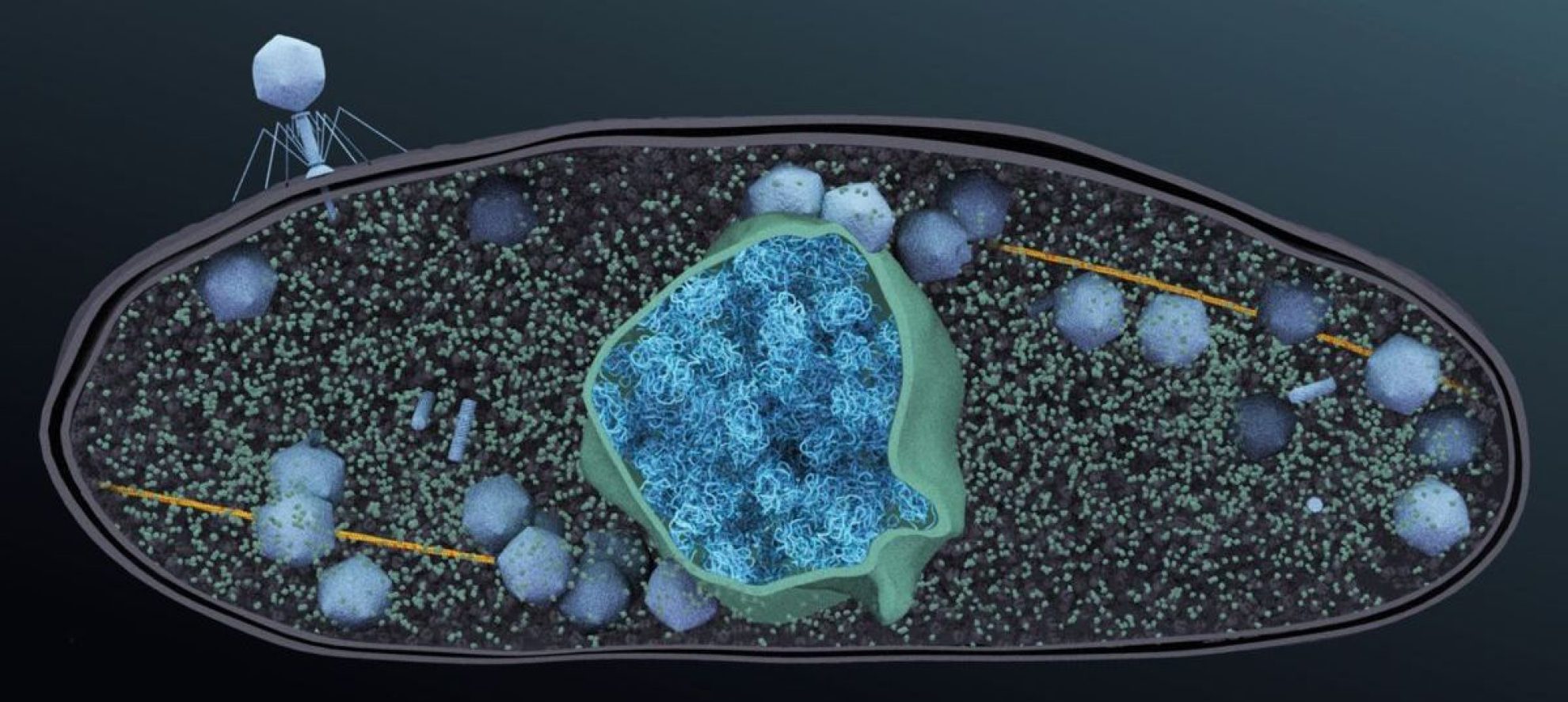

Bacteria encode a wide range of antiphage systems and a subset of these proteins are homologous to components of the human innate immune system. Mammalian nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich repeat containing proteins (NLRs) and bacterial NLR-related proteins use a central NACHT domain to link detection of infection with initiation of an antimicrobial response. Bacterial NACHT proteins provide defense against both DNA and RNA phages. Here we investigate the mechanism of phage detection by the bacterial NLR-related protein bNACHT25 in E. coli. bNACHT25 was specifically activated by Emesvirus ssRNA phages and analysis of MS2 phage escaper mutants that evaded detection revealed a critical role for Coat Protein (CP). A genetic assay showed CP was sufficient to activate bNACHT25 but the two proteins did not directly interact. Instead, we found bNACHT25 requires the host chaperone DnaJ to detect CP and protect against phage. Our data support a model in which bNACHT25 detects a wide range of phages using an indirect mechanism that may involve guarding a host cell process rather than binding a specific phage-derived molecule.

Background from the paper: The coevolution of bacteria and their viruses, bacteriophages (phages), has led bacteria to evolve diverse antiphage systems that halt infection. These systems can be a single gene or an operon of genes whose products cooperate to sense phage, amplify that signal, and activate an effector response that is antiviral [1,2]. Antiphage systems are distributed in the pangenome for each bacterial species and any one bacterial strain has a subset of these systems, which tend to colocalize and move between bacteria within mobile genetic elements [3–5]. The collection of antiphage systems within a given bacterium is referred to as the bacterial immune system [1,2].

Bacterial antiphage systems, like all immune pathways, can be categorized as adaptive or innate. Adaptive immune systems, such as CRISPR-Cas, are targeted to specific pathogens and specialize as a result of previous exposure or “immunization”. Innate immune systems, on the other hand, target a wide range of pathogens in their native form by detecting conserved features. In this way, innate immune pathways act as the first line of defense.

One component of the innate immune systems of humans, plants, and bacteria are nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing proteins (NLRs) [6–9]. These proteins are grouped based on their gross similarity to each other, i.e., inclusion of a nucleotide binding domain and leucine-rich repeats, however, their evolutionary histories and relatedness are complicated. The nucleotide binding domains of all NLRs belong to the STAND NTPase family, which can be further subdivided into related but distinct sister clades [10]. Human NLRs (such as NLRC4, NLRP3, and other components of inflammasomes) use NACHT modules [11]. Plant NLRs (such as ZAR1 and other R-proteins that form the resistosome) use NB-ARC modules, a subclass of AP-ATPases [10,12]. Previously, we found that bacteria encode NACHT modules in open reading frames with leucine-rich repeats, these are bona fide bacterial NLRs [9]. In addition, bacteria encode many NACHT modules in proteins with other domains in place of leucine-rich repeats. These proteins are “NLR-related” and we used NACHT domains to reconstruct the evolutionary history of how NACHT domains originated in bacteria and were horizontally acquired by eukaryotes [9]. More broadly, bacteria also encode proteins with AP-ATPase modules and other STAND NTPases. Multiple clades of antiviral ATPases/NTPases of the STAND superfamily (AVAST) systems have been described [10,13,14]. In humans, there are also antiviral STAND NTPases that are not NLRs, such as SAMD9 [15,16].

Bacterial NACHT module-containing (bNACHT) proteins, as with all STAND NTPases, have a tripartite domain architecture [9,10]. The C-terminus is a sensing domain, the central NACHT domain enables oligomerization and signal transduction, and the N-terminus is an effector domain. While the effector domain function can often be predicted bioinformatically [17] (e.g., identification of a nuclease domain suggests the antiphage system targets phage/host DNA), the stimuli that activates bNACHT proteins is challenging to discover.

We investigated the mechanism of phage detection by bNACHT proteins. Specifically, we focused on sensing of RNA phage because bNACHT proteins are some of the only known bacterial innate immune pathways identified that are capable of protecting against RNA phage. We found that bNACHT25 is indirectly activated by the coat protein (CP) of the model ssRNA phage MS2, which suggests that host cell processes or components are required for sensing. Our analysis led us to discover that activation of bNACHT25 by phage or CP requires the host chaperone DnaJ.

https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3003203